In a time where the devaluation of music seems to be at it’s peak, fans and audiences expect every release to be either for free or donation based, which forces musicians to tour extensively or resort to day jobs in order to support themselves. Deru, an electronic artist who questions this establishment, explores an innovative release of his latest album, 1979. His approach influences listeners to place themselves in an appropriate listening environment, delivering an entirely new experience.

To help him with his vision, Deru enlisted a team of people including the visual artist, Effixx, who collaborated previously on the Outliers, Iceland: Vol. 1project.

I sat with Deru & Effixx to discuss the themes and concept behind 1979:

ISO50: Deru, who is Jackson Sonnanfeld-Arden and how did he inspire your upcoming fifth studio release, 1979?

Deru: Some concepts seemed to coincide thematically when I began working on 1979. A few significant life events caused me to look at photographs differently than I was used to, plus the emotional authenticity of the original artifact that I found at the flea market in Glendale made me realize that I had to make it public and share it somehow. The ideas presented in the philosophy of Jackson Sonnanfeld-Arden deeply resonated with me and I found solace in his words during that time. Jackson Arden was a man who was searching for truth in memories and as I recorded 1979 to cassette tape, the nostalgia and warmth of the medium seemed to go hand-in-hand with the experience of reading these letters.

ISO50: Deru & Effixx, Henry Jackson’s interpretation of his grandfather’s (Jackson Sonnafeld-Arden) manuscripts that mention the Unification Philosophy states that “this solid, mundane world we live in is actually just a memory of a previous universe”. To what extent did this theory influence the feelings of nostalgia you were trying to provoke with this project (both musically and visually)?

Effixx: When I first read and tried to parse these types of sweeping, declarative philosophical statements in his letters, I couldn’t decide whether it was new-agey diatribe or some sort of brilliant quantum theory. Ultimately, it’s probably both. There’s something very romantic about the obvious fact that this man was feeling near the end of his life but was trying to make sense of his memories through the lens of this kind of “holographic universe” way of describing the inevitable cycle of life and death. It’s compelling in that there’s nothing very sophisticated about the words he chooses by today’s standards, but considering that at the time of writing it predates modern quantum physics… that’s very powerful. I definitely owe David Chun for making those connections. He’s the writer/mythologist/researcher in Los Angeles responsible for helping us make sense of the documents.

So as it applies to nostalgia and the visual side of the project, to me it affirmed the idea that photographs and other types of documented memories are a sort of spiritual / anthropological record that equal more than the sum of their parts. Regardless of the technology used to capture the memory, in a metaphysical sense – these frozen moments give us the ability to understand the innate properties of emotion in time and space. Not just simply the matter which occupies the “frame”. Again, not entirely novel concepts in today’s world but pretty transcendent for the time.

Deru: As Anthony suggested, Jackson Arden’s words are somehow both grandiose and simple in their tone. He makes sweeping statements that also hold subtle truths, so they can’t be overlooked quickly and require examination.

There were many aspects within the box that made me want to explore nostalgia however, so even without his texts I would have, but somehow his words made me dig deeper to try to understand some of the shared emotions amongst all of us. Nostalgia, for one, always seems to come with a bitter-sweet quality that I love aesthetically. The heart-ache for home, and not just the physical home, but a return to simplicity, to love.

ISO50: Deru & Effixx, continuing with the the themes of nostalgia and memories, on the 1979 website, people can submit their own images and stories to a gallery. Will you share a few of your favorites and why?

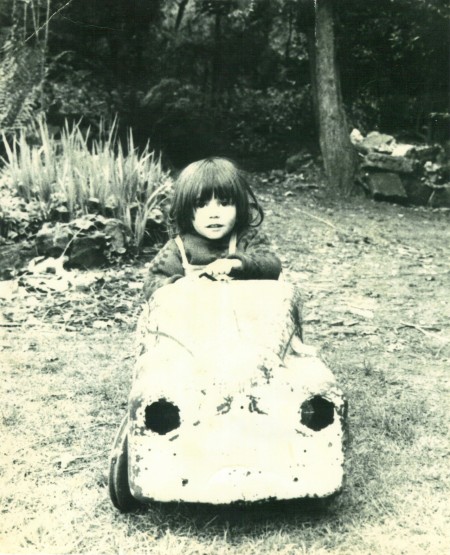

Effixx: I love the Amon Tobin childhood shot for how stark the photo is, and because he describes what I think is a really interesting common theme: recognizing his son (the cycle) in himself.

Lara Howenstine submitted some really beautifully antiquated photos from an aesthetic point of view, and one of the photos depicts an incredibly intimate and vulnerable moment in her life – literally her aunt at her death bed, surrounded by family. That willingness to share such personal moments for the sake of this art project have made the whole thing touching in ways I couldn’t have imagined.

Deru: I’m floored not just by the imagery people have been submitting, but also by the words that they’ve been writing along with them. I’m amazed and grateful for the willingness of people to share such intimate moments from their lives.

The whole project has reaffirmed something that I’ve believed for a while: that people are smart. I feel like as a society we’re taught to think that people are dumb. This mostly comes in the form of advertisements that are so base and transparent that it’s appalling to me that people think they can actually work (which is a whole other topic I know). But there were times while we were making this project that I wasn’t sure if people would get it, that they’d miss the point, as quite frankly this isn’t an obvious project conceptually. We built it in layers so that someone could go in as deeply as they wanted to, but it still requires time to fully digest. It was such a nice surprise then when people started submitting memories even minutes after the site went live that were perfectly in line with the sentiments of the project. And we haven’t received a single submission that didn’t nail the spirit of what we’re asking for, which blows my mind.

It’s also clear to me now that people want to share their lives, and they’ll do so in an open and honest way if they’re given a respectful environment to do so, even in front of total strangers (which interestingly only makes them more empowered).

In particular, Ana G. Noris, entry is incredibly powerful. The honesty with which she talks about her relationship to her brother is so moving. I feel as though I can experience the loss and complexity of her relationship with her brother. I empathize instantly.

ISO50: Effixx, mysticism and the supernatural seem to be prevalent themes throughout your work. How did such a wealth of source material found in Jackson’s original Obverse Box contribute to your fascination with these themes and how did they inspire the visual identity of this project?

Effixx: The original box was a wellspring of inspiration, especially after we got David involved in putting some historical pieces together. In terms of my fascination with mysticism – archetypal stories are really my obsession. Whether you want to call it mysticism, supernatural, parapsychology… I’m interested in the intersection of science and the occult. Where Joseph Campbell meets Aldous Huxley. Many of my peers are obsessed with the future, data, tools that create visual compositions which cannot be created by the human hand. Me, I find much more inspiration in learning from the past and identifying patterns in human behavior.

The other connection to my creative process and trying to assembles a narrative around the pieces of the Arden philosophy and my own process of storytelling is that looking back at other work I’ve recently done… I tend to use historical documents and found footage quite a bit as source material. Most obviously in the Scenic video for Take – Begin End Begin, where we created montaged scenes sourced from a box of found 35mm negatives to tell a story. I feel like it could be due to using the limited resources at my disposal, production-wise, but also because I grew up inspired by artists like Boards of Canada who would use these disembodied fragments of recordings and kaleidoscopic imagery that summoned vaguely nostalgic scenes.

ISO50: Deru & Effixx, can you explain what your version of The Obverse Box is and what it contains?

Deru: We view it as an instrument for extending my album and the visual concepts associated with it into each users unique physical space. One of the nice things about projection is that it changes drastically depending on where it’s projected, which makes the experience most rewarding when it’s an interactive one of experimentation of surfaces and textures to project onto.

We were also inspired by the idea of what a modern day time-capsule could be, and the idea that memories could come alive with light, making them available for interactions, almost in the way real memories are malleable depending upon time, mood, circumstance, etc.

Effixx: I’d echo what Deru said, adding that the format of this thing really makes it unique. When we first started designing the box with Mark Wisniowski, we were kind of dumbfounded that previously it had only been seen as an office / business appliance. Nobody’s really used it as an entertainment tool or in the context of an art project. Particularly in a time where projection mapping has become so popular, this struck me as novel. We went back and forth about whether the SD card slot should be concealed and made permanently fixed to our content and ultimately we chose to leave it open for owners of the box to add their own material. In this way, I think The Obverse Box is a beautiful sculptural object that encourages people to take a body of memories with them wherever they want and create an experience for themselves in an unlikely place. I can’t wait to take it camping with me.

ISO50: Deru, can you talk about the design and manufacturing process that went into creating The Obverse Box?

Deru: Before the design process even began I spent about six months researching, calling strangers, e-mailing big companies, and generally reaching out to everyone I thought might be relevant to try to see if this was even possible. There were many times where it seemed like it wasn’t. I explored all options, and judging by the amount of times I hit roadblocks, I can safely say that this is a really hard thing to do. The world of electronics is just not set up for small-batch runs, or art projects in general really.

But once I’d found a component manufacturer that was willing to work with me, the design of the case was amazingly fun. Mark Wisniowski (also an Outliers: Iceland alum) designed the case, and he rose to the challenge in such a beautiful way. It’s so fun working with your friends when they turn around and blow you away. Once Mark had a few versions of the case modeled in 3D I then found Roberto Crespo, who did all of the 3D engineering for the project. He took Mark’s designs and got them ready for Jon Mendez, who did all of the machining and milling on the project. I could not have found two better guys than Roberto and Jon. Roberto worked for JPL for years and has literally designed circuit boards that are on the Mars Curiosity Rover right now, and Jon is an absolute artist. He worked for the architect Jorge Pardo for years, and taught at The Art Center of Design in Pasadena. He’s also manufactured some really high-profile projects that I probably shouldn’t talk about… But I went back and forth with these two guys honing every aspect of the walnut case for the better part of a year. The case is CNC’d from a single block of walnut. It’s walls are ⅛” thick, and the vents are laser cut. Every part of making this was an exploration into what was possible, and in the end I’m so proud to show the world that we did. There is something so exciting about producing a physical object; about seeing something on the computer screen one minute and in your hand the next. I want to do more of this.

ISO50: Effixx, can you talk to us about the design philosophy and inspiration that went into 1979.la?

Effixx: In terms of developing the design language, I started off with paint, ink, and paper. From the beginning, I felt the main visual objects defining the project should be terrestrial and monolithic. The Obverse Box could be from the past or the future. The main 1979 “thumbprint” was one of many painted shapes that were scanned during these experiments. So, real textural objects were important because they turn graphic when light/shadow is introduced. It’s amazing how many different shapes and contours emerge as expressive marks when the light source and angle are modified. The nine gold strips, the roman numerals which make an appearance on the projector’s splash screen, the thumbprint, the gold dust and splatter… those were the most fun to use as a family of graphics throughout the materials because their origins are so obviously created by the human hand rather than design tools.

The Nine Pure Tones themselves were converted to digital illustrations from Arden’s VERY rough sketches to the sigils we thought he was going for. They’re all pretty clearly inspired by mathematical figures describing reflection, refraction, dispersion, and other phenomena of light and energy presented in physics textbooks. So we arranged them into the loose system Arden laid out and stayed mostly true to what he named each of them (as far as we could read in the documents… they’re pretty illegible).

1979.la is meant to be a repository for all of the ideas behind the entire album, from Arden’s philosophy to Ben’s inpiration, to the user-submitted memory gallery. It’s mostly neutral so that the memories themselves can be the hero. A user can spend time with the articles and letters without emotional signifiers – like color – disrupting the process of interpretation.

What you’ll find making its way into the nine videos themselves is a new element that hasn’t been fully revealed in the website or LP art yet. We’re working heavily with analog video synths and very foundational visual representations of sound/light/energy. They’re meant to be mesmerizing in a way that invites repeated viewing and encourages the user to explore what the patterns and textures look like on different surfaces. Timelessness is what we hope to achieve with the visual language, overall.

ISO50: Deru, in our talk, you mentioned how you feel like music has become devalued in comparison to other art forms. Would you say that with 1979’s release and the ideas surrounding The Obverse Box you hope to instill inspiration among your listeners and place the value back in experiencing music?

Deru: I remember before the internet and mp3’s, buying a new album was a more powerful experience than it is today, at least to me. I don’t hold anything against those two technologies, as they’ve transformed the convenience of acquiring music, but it’s that very convenience that can be so distracting. What I love about the idea of releasing an ambient album on a video projector is that the characteristics inherent in projectors make them perfect for placing the user in the best environment to listen to the music. In other words the act of turning down the lights are preparing for an experience is something that places the person in the best mindset to listen to the music to being with. There’s also something magical about holding light in your hand. Part of the fun of the projector is experimenting with where it pointed and what the light is shining though. Different kinds of glass, fabrics, mirrors, etc, all change the experience hugely.

The devaluation of music is definitely something that I’m trying to address. I know that free music has done wonders for a lot of musicians, which is great, but there’s an aspect to giving away art that you’ve been toiling over for years that’s never felt all that great to me honestly. That’s why on 1979.la we ask for someone to share a memory in exchange for a song. This feels good to me, it feels like an adequate trade.

Selling an object that costs $500 (during the pre-sale) also challenges the idea of what music is worth. Expense depends upon perception. $500 is cheap for art and normal for electronics. It is only considered expensive when viewed as music, which is so devalued now that it’s supposed to be free. This challenges that idea; it challenges the way music is perceived.

ISO50: Deru & Effixx, thank you.

DERU

EFFIXX

FANGX TO ISO50